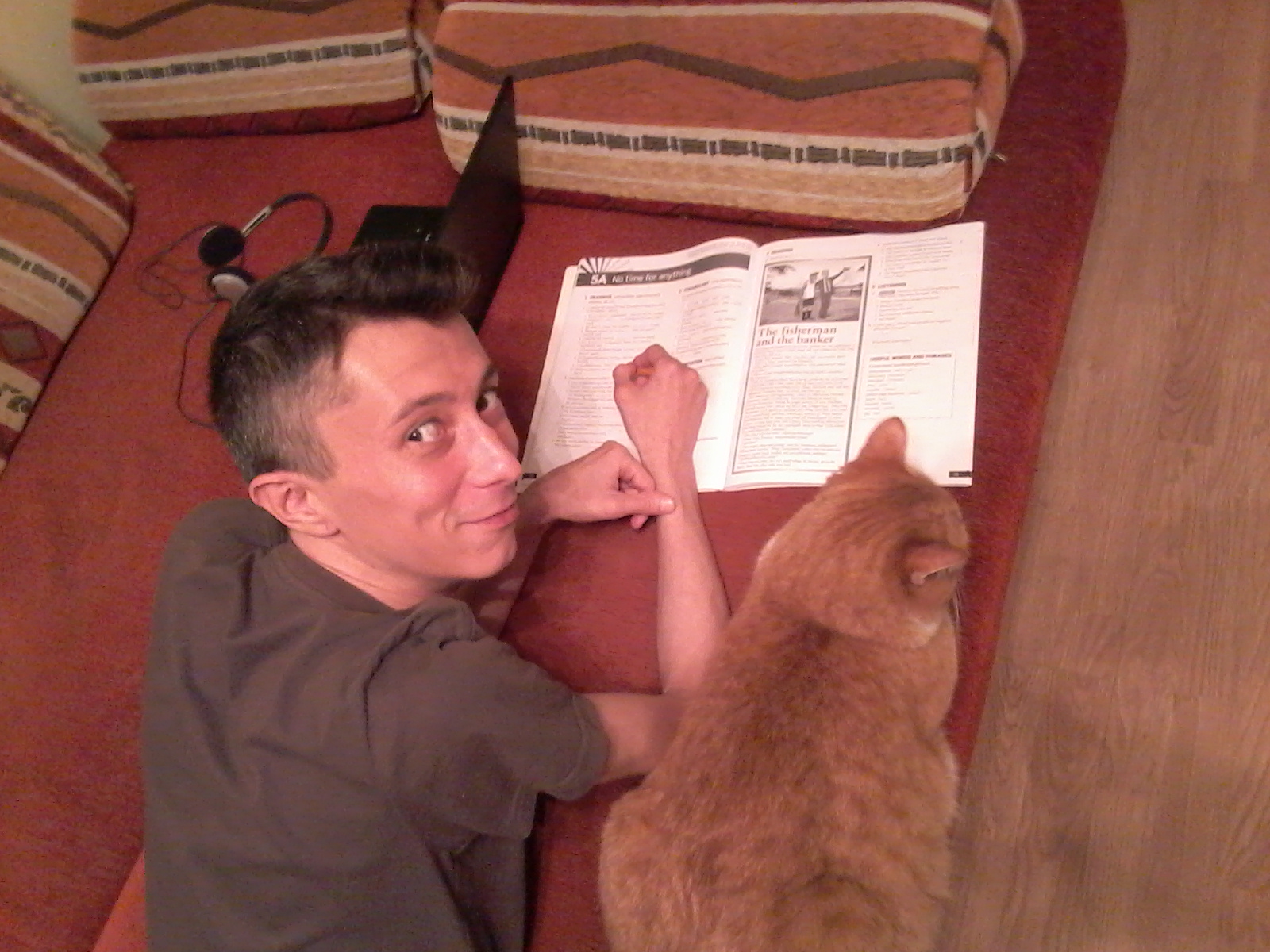

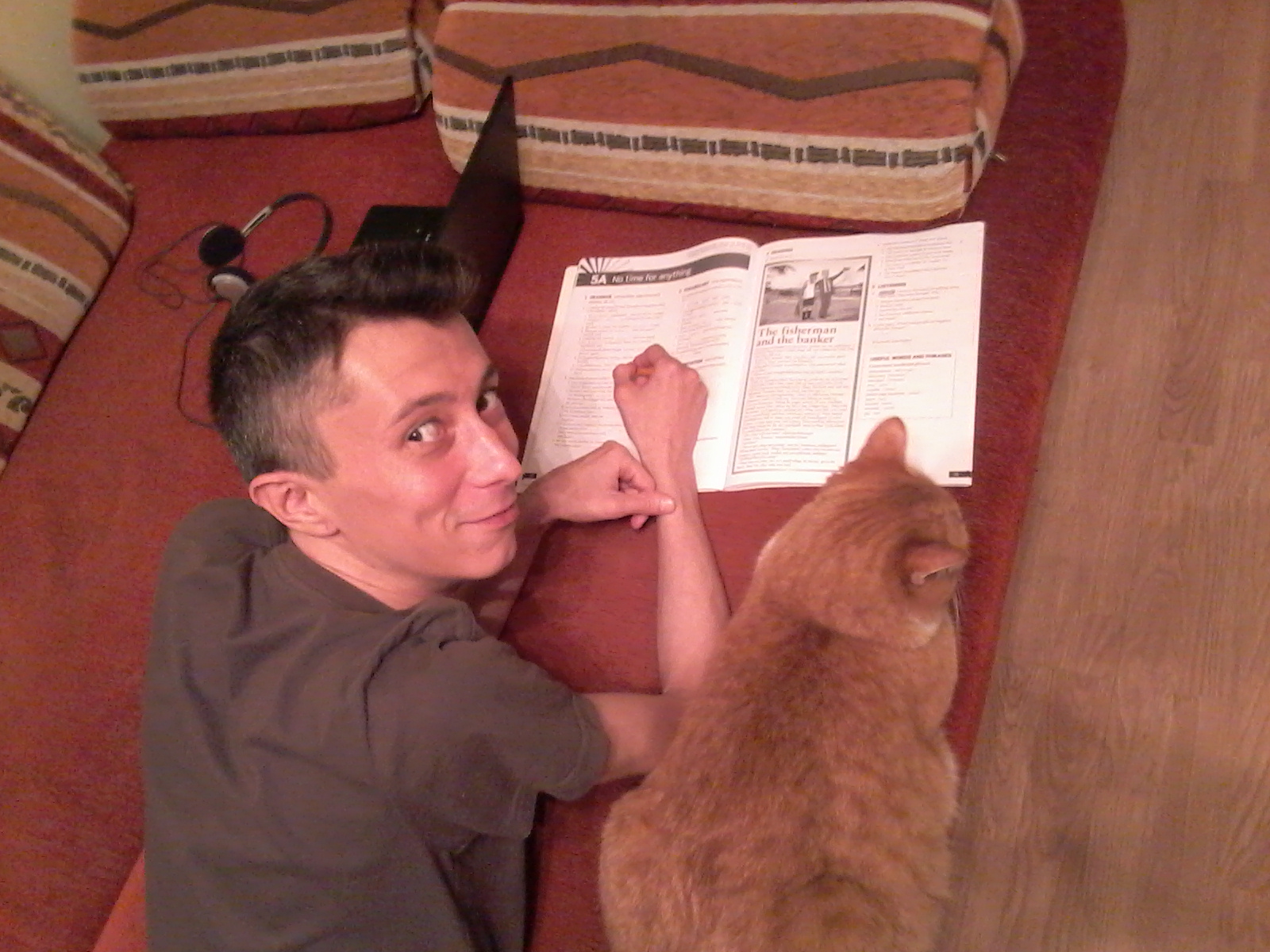

About

Timur Ismagilov was born in 1982 in Ufa (Bashkortostan, Russia). As a child he taught himself to play all the musical instruments that were available at home: the piano and different types of accordion (bayan, talyanka, saratovskaya). He also performed and recorded as a singer of Tatar and Bashkir songs.

Ismagilov started to compose music at the age of 11 and attended Rustem Sabitov's composition class in 1995–2000. He graduated from the Lyceum of Ufa State Institute of Arts (Lyudmila Alexeeva's piano class). In 2005 he graduated from Alexander Tchaikovsky's composition class at the Moscow Conservatory.

In 2005–2008 he took a postgraduate course in the conservatory (his scientific advisor was Svetlana Savenko). The result was a musicological work titled "DSCH. Sketch of a Monograph about the Monogram". An article based on this study was published in Berlin in 2013.

In 2004–2006 Ismagilov kept "the Diary of a Young Composer" on Vladimir Shahidzhanyan's website, besides he composed and recorded music for the latter's computer program "SOLO: Touch Typing Tutor" (100 piano pieces). In 2006 he founded the Sviatoslav Richter's memorial website. He has been organizing contemporary music concerts since 2010, and became one of the composers interviewed by Dmitry Bavilskiy for the book "To be called for: Conversations with contemporary composers" (published in 2014).

Timur Ismagilov's catalogue lists more than fifty works. In his music he combines various composition techniques with a sustained interest in traditional Tatar and Bashkir melodic language. Besides composing his own pieces, Ismagilov has made about 600 arrangements for different sets of instruments.