About

Arts and music in particular are human enterprises of exploration, just as much as Science.

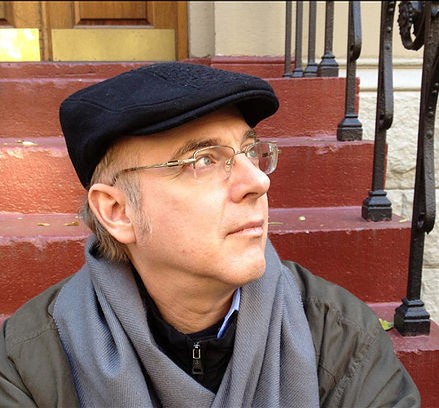

Pianist-Composer Moshe Shlomo Knoll was educated at The Juilliard School in New York, and at the University of Arizona in Tucson, AZ.

He earned the B.M. and M.M. Degrees from Juilliard, having studied Piano with Herbert Stessin, William Masselos and Beveridge Webseter. Dr. Knoll studied Composition at Juilliard with David Diamond and Michael White. He was mentored by Vincent Persichetti and Anthony Newman. At the U.of A. Knoll studied Piano with Ozan Marsh, and Composition with Robert Muczinski and Dan Asia. A virtuoso pianist, Dr. Knoll has been performing his works for three decades to the acclaim of international audiences. One of the highlights of his early career was a 1986 apperance at Lincoln Center's Alice Tully Hall at which Dr. Knoll performed his Piano Sonata #1. In the concert review, Tim Page from the New York Times wrote:

"Mr. Knoll is not just a pianist, but a composer as well, and he plays that way. His interpretations emphasized formal structure and came to most vivd life in the complex passages of the music he played. One of Mr. Knoll's compositions, his Sonata #1, was flashy, melodic, economical, and played with appropriate authority."

Dr. Knoll has had a distinguished career as a Chamber Musician and as a Collaborative Pianist. After training with Professor Miri Singer, from Tel Aviv University, he served as Harpsichordist Continuo and Librarian for the Apollonia Ensemble for Early Music, in Israel. Two of his arrangements were performed at the Israel Festival by the Phoenix Ensemble for Early Music. He has also been active in the field of Jewish Liturgical music, having accompanied the noted Cantors Dov Keren, Simon Cohen and Irwin Goldstein. He has also collaborated with the Zamir Chorale of Boston, under the baton of Maestro Joshua Jacobson.

Dr. Knoll has performed Lieder with the noted German Baritone Johannes Held. He is a founding member of the Fantasia Trio, together with Violinist Laura Jean Goldberg, and Cellist Lori Singer.

Knoll's compositions include Chamber and Vocal works as well as pedagogical material and etudes for piano students of all levels. His compositions have been heard in Venezuela, Brazil, Israel, and in the USA, in NY, Massachusetts, Maine, Arizona and California.

Among recent highlights was a successful performance of his PSALM 133 for Soprano, Violin Obbligato and Strings, featuring soloists Allison Charney, Soprano, and Laura Jean Goldberg, Violin with the San Jose Chamber Orchestra under the baton of Barbara Day Turner. This composition was subsequently performed twice in NYC under the baton of Thomas Elefant.

Dr. Knoll's composition Anthem of Unity, on texts by Meister Eckhart, for Piano Trio and Baritone Solo was premiered in Beverly Hills by UCLA Professor Michael Dean. Knoll's Toccatta in the Phrygian Mode, for Piano and Cello was perfomed by Martin Perry and Misha Veselov at the LyricaFest Chamber Music Festival in Lincoln, MA in 2012. In 2015 ArtsAhimsa presented a Retrospective of Moshe Knoll's works, spanning the years 1975-2014 at The Mary Lea Johnson Performing Arts Center at The Calhoun School in NYC.

Dr. Knoll's String Quartet, "Memories of Novardok" had its world premiere at the concert "I am for my Beloved"

at The Museum at Eldridge Street, in NYC. Moshe S. Knoll is one of the featured composers of the soundtrack for the documentary film "God Knows Where I Am" the Linda Bishop Story (2016), produced by Todd and Jedd Wider, starring actress Lori Singer. The film score was recorded by the Manhattan Symphonie under the baton of Gregory Singer.

Dr. Knoll sits on the board of DAHA, the Dvorak American Heritage Association, and there he serves as Co-Curator of the concert series "Dvorak: The Chamber Music Survey" which will present the complete chamber works of Antonin Dvorak at Bohemian National Hall in NYC. Dr. Knoll has been Composer-in-Residence and Director of Musical Research at ArtsAhimsa since 2012.