Great to have you back!

1

Videos

About

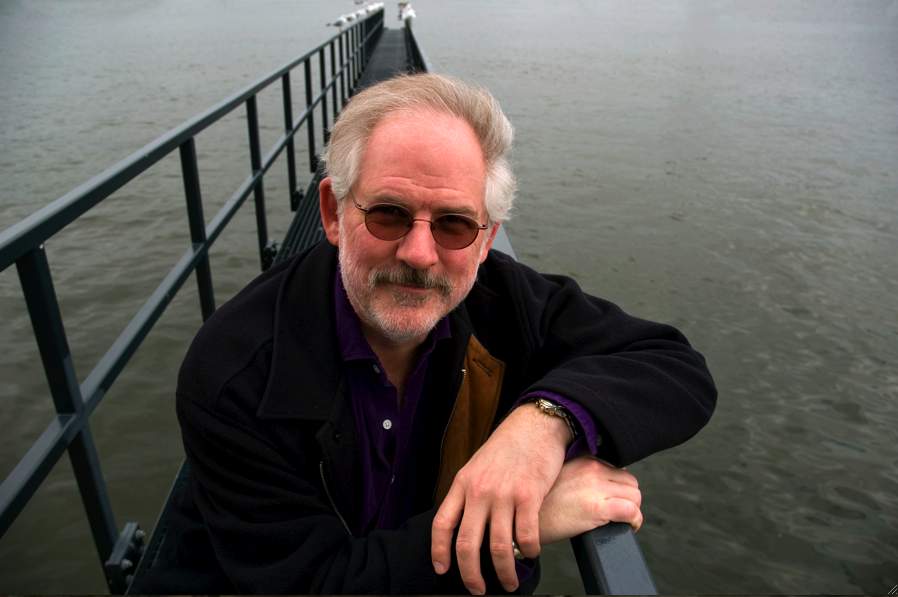

Kyle Gann, born 1955 in Dallas, Texas, is a composer and was new-music critic for the Village Voice from 1986 to 2005. Since 1997 he has taught music theory, history, and composition at Bard College. His books include The Music of Conlon Nancarrow, American Music in the 20th Century, Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice, No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage's 4'33", Robert Ashley, Essays After a Sonata: Charles Ives's Concord, and The Arithmetic of Listening: Tuning Theory and History for the Impractical Musician (forthcoming). Gann studied composition with Ben Johnston, Morton Feldman, and Peter Gena, and his music is often microtonal, using up to 37 pitches per octave. His major works include Sunken City, a piano concerto commissioned by the Orkest de Volharding in Amsterdam; Transcendental Sonnets, a 35-minute work for choir and orchestra commissioned by the Indianapolis Symphonic Choir; Custer and Sitting Bull, a microtonal, one-man music theater work he's performed more than 30 times from Brisbane to Moscow; The Planets, commissioned by the Relache ensemble; and Hyperchromatica for three retuned, computer-driven pianos. In 2007, choreographer Mark Morris made a large-ensemble dance, Looky, from five of Gann's works for Disklavier (computerized player piano). His writings include more than 3000 articles for more than 45 publications, including scholarly articles on La Monte Young, Henry Cowell, John Cage, Edgard Varese, Ben Johnston, Mikel Rouse, John Luther Adams, Dennis Johnson, and other American composers. He was awarded the Peabody Award (2003), the Stagebill Award (1999) and the Deems-Taylor Award (2003) for his writings. His music is available on the New Albion, New World, Cold Blue, Lovely Music, Mode, Other Minds, Innova, Meyer Media, New Tone, Microfest, Vous Ne Revez Pas Encore, Brilliant Classics, and Monroe Street labels. In 2003, the American Music Center awarded Gann its Letter of Distinction, along with Steve Reich, Wayne Shorter, and George Crumb.

Sheets

Interview

What does music mean to you personally?

The ability to build memorable and seductive forms in pitch and time that suggest models for how to live in the world.

Do you agree that music is all about fantasy?

I have always listed imagination as my primary musical virtue, followed next by emotional persuasiveness. So, yes. For some people, craftsmanship, technical innovation, and atmosphere are important, and I respect those viewpoints too.

If you were not a professional musician, would would you have been?

An astrologer. In 1986 I had given up on making money as a music critic, and was about to list myself as an astrologer, when from out of the blue a phone call came from the Village Voice, asking me to apply for their music critic job. I still do charts for a lot of friends.

The classical music audience is getting old, are you worried about your future?

The classical music audience has always been old. Old people go to sedate concerts, young people to more physically demanding events, and it’s been that way as long as anyone’s been keeping track. We need a lot of the classical „canon“ to fall by the wayside, to make room for new works anyway. The classical music world is so trapped in the neurotic, 19th-century German Great Men myth, that not only can it not change or adapt, it can’t even continue growing according to its own internal logic. And I call my music postclassical, not classical. So I’m not worried. People will always need music, and there will always be people who realize that music can be a lot more than just pop songs.

What do you envision the role of classical music to be in the 21 century? Do you see that there is a transformation of this role?

I’m 62, so I don’t have to envision it as far as I used to feel obliged to. When I was young, I thought we would see a lot more notated composition for pop-music instruments, but then it turned out the generation of musicians after mine was rather draconian about keeping pop and classical music separate, so that didn’t happen. I certainly think we need more flexible large ensembles, and need to get away from the mandatory winds/brass/percussion/strings orchestra, which keeps us trapped in an artificial semblance of the 19th century. I also thought, after Brian Eno’s Music for Airports, there might be a wonderful market for site-specific ambient musics, like for restaurants and office buildings, but corporations think we should be able to get by forever on Muzak arrangements of 1960s pop songs. So you can see that nothing I envisioned in my 30s or 40s has come to pass. I could make some tentative predictions about the internet and virtual reality, and then you could bet that they won’t come to pass either.

When I say that classical music is searching for new ways or that the classical music is getting a new face, what would come to your mind?

The growing use of more informal concert spaces and formats is a great thing. A lot of the best new music is not conducive to being trapped in immovable rows of chairs. Creative music need not feel like going to church. I’m always happy to see people writing for ensembles with accordions, electric guitars, synthesizers, and banjos, too, even bagpipes. The classical music mentality we educate young musicians into is stifling.

Do you think that the classical musician today needs to be more creative? Whats the role of creativity in the musical process for you?

I don’t understand the first question, and will answer the second. I am happiest when I can start out with some clash of harmonic and/or rhythmic ideas that shouldn’t work, and then do everything to make it work. I wrote a piece (Medating Daydream) in 6/4, and couldn’t make it work until I changed harmony every five beats. I started an opera (Cinderella’s Bad Magic) in E-flat major with the idea that it would smoothly move into C-double-sharp minor by the end. I wrote a piece (Venus) in 3/4, and put the melody in 25/16 meter. Something that sounds like a terrible idea when you first think of it is likely to be fertile. The things that make sense right away are probably dull.

Do you think we musicians can do something to attract young generation into the classical music concerts? How will you proceed?

I could come up with something anodyne, but the truth is that I’m old enough that I no longer understand the younger generation. So many young composers are now obsessed with angst-ridden, complex European music that sounds old-fashioned to me, some it by composers a generation older than me (like Kurtag and Lachenmann). And unlike my generation, who were greatly indebted to not-yet-famous composers who came just before us (Nancarrow, Feldman, Johnston, Tenney, Robert Ashley, Meredith Monk, Harold Budd), the younger generation seems entirely uninterested in mine, so I feel doubly alienated. All I can do, and have tried to do, is create a more intelligible microtonal musical language than we’ve had before in hopes that young people will hear possibilities they didn’t know were there. That seems to be having some small success, as evidenced by your getting in touch with me.

Tell us about your creative process. Do you have your favorite piece (written by you) How did you start working on it?

The first part I really answered in question 7. I have a lot of more conventional pieces I love, but I think my signature pieces are the two in which I combined microtonality with different tempos simultaneously or alternating, Custer and Sitting Bull (1995-1999) and Hyperchromatica (2015-2017). Custer came out of my involvement with American Indian music, which I used to transcribe recordings and performances of, and often used in my music of the 1980s and early ’90s. In the ‚90s people became sensitive about „appropriating“ music of nonwhite cultures, but since I am a white man I thought I owned Custer as much as anyone could. I collected the tunes connected with the two main characters, including Custer’s signature tune „Garry Owen“ and a sun dance and personal song attributed to Sitting Bull, and tried to be faithful to their less conventional qualities through rhythmic complexities and microtonal scales. Also, I love setting text, and I let the music be completely rhythmically determined by the rhythms of the historical texts I found for them. Speech rhythm is the basis of my vocal music.

Hyperchromatica started because my music was getting no performances, and I defiantly decided to make my most ambitious recording ever (two hours and 36 minutes) with no performers. It’s for three Disklaviers (computer-run player pianos) tuned to a scale with 33 tones to the octave. For years I had been writing microtonal pieces in simple rhythms, and polytempo works in conventional tuning, and was having trouble combining the two again as I had in Custer. Then in summer 2015 the first close-up photos of Pluto came back, and I read that Pluto and Neptune keep up a 3:2 ratio in their orbits, and that other planets have similar simple ratios. That gave me the idea for how to use, in „Orbital Resonance,“ such out-of-phase rhythms with my 33-tone scale, and after that the ideas for the other sixteen movements came very quickly, as though a kink in a hose had been straightened and let the water flow.

We, Moving Classics TV, love the combination of classical music with different disciplines: music and painting, music and cinematography, music and digital art, music and poetry. What do you think about these combinations?

I think they’re wonderful, and I especially think that people are more and more visually oriented these days, so that having some kind of video component to the music helps the music to be more accepted (not necessarily more understood). However, my talents are only for auditory imagination. I’ve had videos made to my music, but only after the fact, because I wouldn’t know how to collaborate. I have also spent my life writing about music, because millions of people get meaning more easily from words than music, and can start to understand peculiar music with a few words to push them in the right direction.

Can you give some advice for young people who want to discover classical music for themselves?

DON’T LISTEN TO THE CONVENTIONAL TASTE-MAKERS, EVER. Don’t read classical music books (except for mine, of course). Start out with the weirdos, like Harry Partch and Erik Satie and Conlon Nancarrow and Maria De Alvear and Harry Bertoia and Harold Budd and Annea Lockwood and Mikel Rouse and Kaikhosru Sorabji and Charlemagne Palestine and Moondog, and they will lead you to the periphery of the classical music world, where all the frowned-upon, „illegitimate,“ exciting composers are. Prizes are given to those who conform to the status quo, and mean nothing. Composers who get performed frequently at large institutions do so because their music is easy (cheap) to rehearse, not because anyone loves it. Assume that the classical music world is an upside-down meritocracy, with all the amazing people at the bottom, at least during their lifetimes. Remember that when Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande was premiered, the Paris Conservatoire professors forbade their music students to attend; they had done the same thing with Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique in 1830. There is a hell of a lot of good new music out there, and it’s difficult to find amid all the heavily publicized crap. The names above are starting points for some of the paths to the real stuff.

Now it is a common practice in the media to talk that the classical music is getting into the consumption business, do you agree? We are speaking about the supply and demand rules and how to sell your “product” in your case your compositions. How do you see it?

Well, I did recently hire a publicist. I’m of two minds. Having grown up in the pre-Reagan era before capitalism became toxic, I still think there’s nothing wrong with „selling“ one’s music, which was feasible back when the corporations were reined in by regulations. Until 1980, it wasn’t that hard for whacko composers to get major record deals. I sentimentally assume that maybe that world will return, and it probably won’t. Capitalism now probably needs to be destroyed, and it is difficult to foresee how we will get our music out in whatever system replaces it, except insofar as we’re already doing it on the internet. It would certainly help if the classical music world quit colluding with the corporations by sticking to the Great Men paradigm by which there are only a few good composers per generation, and they produce all the music worth hearing. It’s very difficult right now. I’m lucky I have a secure teaching job, but I know so many fantastic composers basically living in poverty. Using the internet and with the help of friends, they still manage against tremendous odds to get their music out there, but not to make money from it.

Do you have expectations what regards your listeners, your audience?

Many. I assume that they will appreciate a good tune, or a catchy rhythm, and that if I can lure them in with something understandable on the surface, they will put up with and even enjoy the weird stuff I put in the background. I assume that they’re eager to discover fun, exciting new music, but not music that puts up tremendous hurdles to their comprehension. I never feel I’m writing down to the audience, because as a listener I enjoy the same things they do. I just also enjoy some things they haven’t heard yet, and I’m determined to sneak those in too. I got into classical music as a child, and modern music at the age of 13, long before any college professors tried to influence me, and I remember what naive listening is like, and how important, even inevitable, it has to be. As a result, I tend to get more positive and insightful comments from non-musicians than from my fellow composers.

What projects are coming up? Do you experiment in your projects?

I have no upcoming projects. I finished two books and two CDs, including my most ambitious work ever, in the last three years, and I’m mentally exhausted. Plus, I have no commissions anyway, and little to no public interest in my work. I would like to think I’ll get a second wind at some point, but if I don’t, I’m not sure anyone will notice. I do think I experiment in nearly every work, though sometimes performance constraints lead me to experiment in fairly subtle areas. Some of my music looks so simple on the page that performers don’t give it enough rehearsal, and they invariably find that it’s harder to play than it looks, usually because my underlying rhythmic concepts are pretty unusual even when I’m only using quarter- and 8th-notes. I’m a great believer in what Mozart called „the artless art,“ in which the innovative technical feats are underneath the surface, not paraded in the foreground to show off. The aim should be to delight the audience, not make the composer look smart.

Copyrights © 2019 Moving Classics TV All Rights Reserved.